University of South Florida (USF) archaeologists are not only changing the way that archaeology is done, but are changing the way we teach and learn with 3D scanning and reverse engineering

By Dr Lori Collins, University of South Florida

May 2011. University of South Florida (USF) archaeologists are not only changing the way that archaeology is done, but are changing the way we teach and learn about archaeology as well. Researchers Drs. Travis Doering and Lori Collins are using laser scanners, GPS, and geophysical imaging to document the past without the need to dig, remove, or destroy anything. Yet, they are able to quite literally bring the past to life for their students, transporting 3D archaeology into the classroom and allowing students to virtually visit sites and examine artifacts from exotic locales across the globe or from little known places in their own backyards.

Doering and Collins are Co-Directors of the Alliance for Integrated Spatial Technologies (AIST), a Core Facility at USF that specializes in applied interdisciplinary research in three dimensional & spatial documentation and analysis. AIST brings together students and researchers from multiple disciplines through the use of spatial sciences to examine and solve real-world issues, and to educate and make research more accessible to students. A major use of these new technologies is to preserve and better understand our natural and cultural heritage.

A recent example of their heritage preservation work took place at the world famous archaeological site of La Venta, located in Tabasco, Mexico. La Venta is pre-Columbian civic-ceremonial center of the Southern Gulf Coast Olmec civilization that dates to around 900 to 400 BC. The site was first excavated during National Geographic Society sponsored explorations in the early 1940s by renowned archaeologist Matthew Stirling. He uncovered monumental carved stone colossal heads and other monolithic stone objects that, along with exotic items, would come to define the Olmec art-style. Doering and Collins, along with their colleague Dr. Mary Pohl from Florida State University, used laser scanners and photographic techniques to record, analyze, preserve and protect many of these important monuments. In 2007, the trio visited the archaeological site and Mexican museums where the sculptures reside, and with permission from Mexico’s Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH) document more than 20 of the monuments in a first phase of this on-going research. Work continues to expand the identification, description, and interpretation of these Olmec carvings. Pohl is studying early Mesoamerican writing systems and uses the scan data to compare and contrast the carved iconographic elements.

The types of data collected during this work are considered the best available documentation methods for archiving and analyzing carved stone monuments. The 3D data and images are being shared with archaeologists and researchers to better interpret and understand ancient Olmec communication systems. These data are also being used to teach classes in heritage and museum studies, allowing

students to learn about the ancient past in new and innovative ways, including 3D renderings and models, 3D printing of objects, and virtual site visitation.

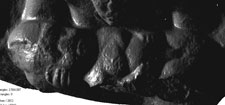

Initially, Doering and Collins used close-range 3D laser scanning with an accuracy of .05mm (approximately half the thickness of a human hair), to capture the La Venta sculpture. They have since continued to improve, expand, and enhance their repertoire of innovative documentation and analytical techniques. At other Olmec sites in Mesoamerica, they have added advanced photographic imaging techniques such as Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) and other progressive forms of photographic analyses to provide details about surface treatment, stone weathering, ancient and modern modifications to the stone. Through the integration and development of multiple data acquisition and processing techniques they have been able to resurrect previously indistinct or indeterminate carved details and make them observable in ways not previously possible.

All these technologies are allowing researchers to “see” the ancient stories that were carved in stone and, in so doing, develop new appreciations and better understandings of the meanings of these sculptures and their relationships to other culturally related sites.

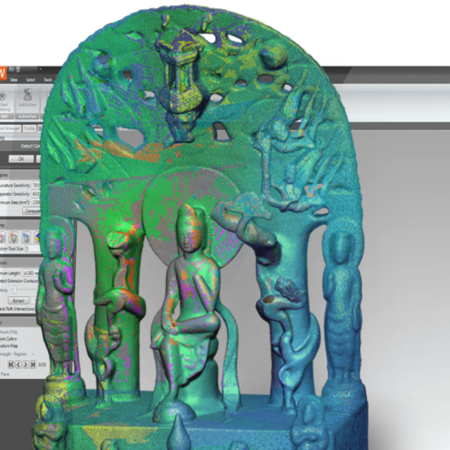

Post-processing of the sculpture data in USF-AIST visualization laboratories involves the use Geomagic software to create 3D models and surface elevation models (SEM) that show carved elements in new and better ways, and the software allows texture maps using high-resolution photography to overlay the 3D surface. Students can then view the sculptures in high resolution as well as manipulate the pieces to examine dimension and surface metrology and virtually rake light across the pieces to bring out details that are difficult or impossible to see any other way.

Students have even created objects from the data, with the ability to construct models in Geomagic software for 3D printing. “The 3D printing from the scan data is an incredible experience for students who may never get to see the real artifact, which is often held in vaults or inaccessible locations”, Collins says, “but with the 3D printed object we can examine the artifact first hand and not be afraid to pass it around in class.” Collins teaches courses in the Department of Anthropology such as “Technology for Heritage Preservation”, and “Museum Informatics,” which she co-teaches with Doering. She feels that these new ways of doing, experiencing, and teaching archaeology, heritage preservation, and museum studies are having a democratizing effect for students. “Students may never get the experience of traveling to archaeological sites and museums, but through 3D laser scanning and other spatial and imaging techniques and software visualizations, we can bring the archaeology of the world to them”.

University of South Florida archeologists Drs. Travis Doering and Lori Collins use 3D laser scanning and software modeling techniques to document Altar 5 from the site of La Venta in Tabasco, MX

Doering and Collins use computers and 3D laser scanners rather than shovels and trowels to conduct archeological research, exploration and analysis.

3D model of Altar 5 at La Venta using Geomagic Wrap allows details, such as the necklace and headdress on the infant figure to be seen and identified for the first time

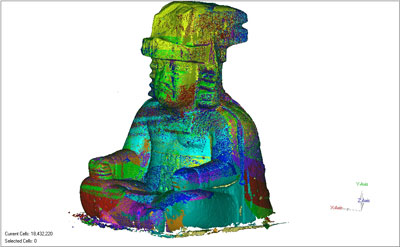

AIST used the Konica Minolta scanner to document a La Venta sculpture that is curated at the Museo Regional de Antropologia Carlos Pellicer Camara in Mexico

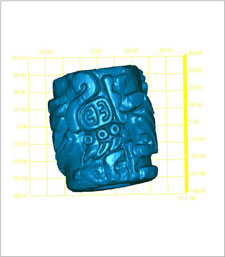

The San Andreas Ceramic Roller Seal, found near La Venta, was documented and modeled in 3D using Geomagic Wrap, and the data brought back to the University for use in the classroom.

Using the 3D data, students at Collins' Technology for Heritage Preservation make 3D prints which are used for teaching and interpretation. Collins says having a tangible item to see, use and feel is an incredible part of the teaching experience, especially for artifacts that are held in museums and are not easily accessible.